June Meeting – Book Recommendations

This was Susan Godlington’s idea – what a great meeting! The books members chose to recommend included poetry and novels, history, inspiration, books they learned to spin or weave from, and books they go to when planning a project. I’ve put all of the recommendations into a booklist:

HGWSD June books

Catherine Freeland had trouble just selecting one or two to talk about, but chose first the book she used when starting to weave: Rachel Brown: “The Weaving, Spinning and Dyeing Book”. Very well used as you will see from the pictures! This is excellent for all types of looms. Her next book was “Knitting in America”. The author Melanie Falick travelled all over America, North and South, collecting information and profiling knitters, spinners, weavers and fibre producers. Catherine also spoke of being inspired by the work of Sheila Hicks as it has developed over the years. She mentioned: “Weaving as Metaphor”, which shows Sheila Hicks’ work over a 50-year period. (This is on Amazon at a truly astonishing price!) Catherine sent me details of the above books after the meeting and added the following recommendations from her bookshelf: Anni Albers: “On Weaving”; Peter Collingwood – anything of his; Clara Creager: ”All About Weaving: a comprehensive guide to the craft” (occasionally seen in second-hand shops); Bernat Klein: “Bernat Klein, Textile Designer, Artist, Colourist” – tweed design, colour and texture; Jenny Dean: “Wild Colour”; Jill Goodwin: “A Dyer’s Manual”.

Hilma read a poem from “Weaving Songs” by Donald S Murray. This little gem of a book has photos of tweed production on the Isle of Lewis interwoven with Donald’s poems. Hilma’s second book was “The Big Book of Weaving”. This has excellent instructions for projects and the practicalities of setting up a loom.

Ann Johnson used “The Essentials of Handspinning” by Mabel Ross when she first learned to spin. Her second book was “The Shetland Dye Book”, which has basic recipes using native plants, and including their local names (e.g bracken = trowie cairds). It also has a list of plants to include in a dye garden. Ann also recommended: Harriet Tidball: “Woollens and Tweeds”, which looks at the evolution of patterns and includes pattern drafts for some of the estate tweeds. She showed us a well illustrated book on fungi: “The Mushroom Book”, but said even with this it was difficult to distinguish between similar fungi and identify those best for dyeing. Later in the afternoon she added a light note with “Pocket Pompoms”!

Serena recommended “A Stash of One’s Own”, a collection of essays, edited by Clara Parkes, in which people like us talk about their yarn and fibre stash habit! She also recommended: “The Secret Lives of Colour” by Kassia St Clair, and “Indigo: Egyptian Mummies to Blue Jeans” by Jenny Balfour-Paul.

Denise recommended “The Book of Looms: A History of the Handloom from Ancient Times to the Present” by Eric Broudy. This is quite an old book, but when I looked on the web it seems it’s being re-issued in September this year. “Byways in Handweaving” by Mary Meigs Atwater deals with card weaving and inkle weaving, and includes patterns from Scandinavia and South America. Another old and prized book Denise recommended is “The Colour Cauldron” by Sue Grierson. This scholarly work is about the history of natural dyes and dyeing in Scotland, with notes on the plants, and the process Sue used to extract the dye and the colours she got. It has been out of print for some years. A spinning book Denise particularly values is: “Spin Control” by Amy King – excellent for making you think about what you are trying to produce. For knitters Denise recommended “Kaffe Fassett’s Pattern Library”.

Aileen said if she could only keep one book it would be: “Traditional Fair Isle Knitting” by Sheila McGregor.

Fiona Recommended “Colour Works” by Deb Menz. This is an excellent book about colour relationships and helps you think about how colours work together. Her other book was: “Scottish Home Industries” by Alexander Ross, first published on 1895, reprinted in 1975. It includes spinning weaving and dyeing, as well as a range of other crafts. Fiona also showed us a beautiful book about woad: “Le Pastel en pays d’oc” by Sandrine Banessey. It is printed in French and English.

The book Andi goes to for ideas is: “The Handweaver’s Pattern Book” by Marguerite Davison. This has a complete range of patterns for 4-shaft looms. For 8-shaft she uses “The Weaver’s Book of 8-Shaft Patterns” by Carol Strickler, which is an excellent basic ideas book. She had bought “Weaving with Echo and Iris” by Marian Stubenitsky, but needed the On-Line Guild course with the author to really understand it. For inspiration she showed us “World Textiles” by John Gillow and Bryan Sentence – lots of colour pictures illustrating a wide variety of textile techniques from around the world.

Mary Paren recommended “Learning to Weave” by Deborah Chandler. She used this when first learning to weave, and still finds it useful. Her next book was “The Spinner’s Book of Yarn Designs” by Sarah Anderson. Starting with basic fibre preparation and drafting techniques the book moves on to plying techniques, then to a wide range of yarn designs, with clear photographs to show the desired end results, and worked samples. “The Fleece and Fibre Sourcebook” by Deborah Robson is excellent for information on what a fleece from a particular breed should be like and how it should spin. As the book is American it doesn’t include all of the UK rare breeds. As a beginner spinner Mary found a lot of helpful information in “Learn to Spin” by Ann Field. Later Mary mentioned “This Golden Fleece: a Journey through Britain’s knitted history” by Esther Rutter

Norah’s first book was “Threads of Life” by Clare Hunter. This books gathers examples of how people from many countries and at different times in history have used stitching to express themselves, and to help them survive in difficult circumstances. “The Art of Tapestry Weaving” by Rebecca Mezoff is an in-depth guide to tapestry weaving. Norah’s third book is Alden Amos’ “Big Book of Handspinning, which she likes because it is irreverent and debunks a lot of received wisdom!

Sheila Munro, who has done a lot of spindle spinning recommends “Respect the Spindle” by Abby Franquemont. For weaving, in addition to books already mentioned by others: “Doubleweave” by Jennifer Moore. This book shows very clearly how doubleweave works, and has a sampler for 4-shaft, which works through a variety of techniques. It also includes several projects for 4-shaft and 8-shaft looms.

“Yarn-i-tec-ture” by Jillian Moreno, Liz’s choice, describes itself as a knitter’s guide to spinning, and aims to help you produce the yarn you want for your knitting project. It has information about different fibres and fibre preparations and how to work with them, and lots of samples.

The book Susan spoke about first is: “Colour: travels through the paintbox” by Victoria Finlay, a social anthropologist. The book is a history of paint colours – when and where they were discovered and how used, starting with ochre and cave paintings – a book to read rather than use for reference. Susan also mentioned “In the Footsteps of Sheep” by Debbie Zawinski. The author walked through Scotland, collecting and spinning fleeced and knitting socks. “The Indigo Girl” by Natasha Boyd is a fictionalised account of the true story of a young woman in South Carolina in the 18th century who learned to produce indigo dye to save her family estates.

My own suggestions? “Women’s Work: the first 20,000 years” by Elizabeth Wayland Barber. This is a history of textile production from Neolithic times to Classical Greece. The author is an archaeologist and also a weaver, and writes with understanding of the processes involved. It’s a very readable book. Mary has another book by the same author, which I’ve included in the booklist: “The Mummies of Urumchi”. “The Wool Pack” by Cynthia Harnett is a book for young teenagers first published in 1951. It has a lot of historical detail about the wool trade in the late 15th century, this considerably reduces its appeal for youngsters, but makes it an interesting light read for adults interested in textiles.

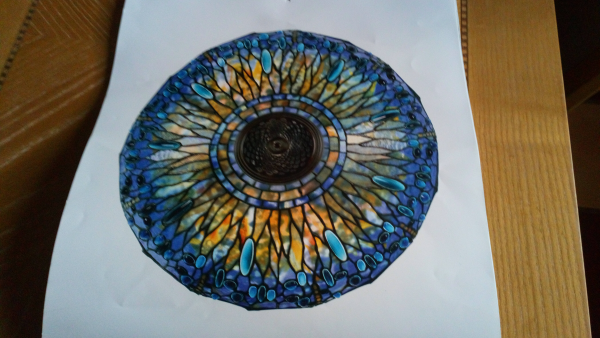

Pictures (sorry about the quality, some did not show up well on screen):

[envira-gallery id=”4558″]

In the afternoon session first Norah showed us the miniature tapestries her school pupils had worked then she and Hilma showed us the results of their solar dyeing. Hilma had a good green from the wallflowers she started off as a demonstration at last month’s workshop, and lovely results from her layered skeins. Norah had good colour from daffodils, and mixed results from lichen – one jar showed an interesting pink, one a deep blue green, and the other no colour at all! Liz had some great results from indigo dye experiments, and some very chunky arm-knitted rugs. Sheila was spinning a black and red batt. Norah got some helpful tips from Denise on steeking for the Fair Isle pattern she is knitting; she also showed us a box of fibre from different sheep breeds that she’s bought in preparation for Tour de Fleece.

[envira-gallery id=”4608”]